How a group of Virginia Baptists fought for religious liberty for people of all faiths or no faith.

The Formative Years

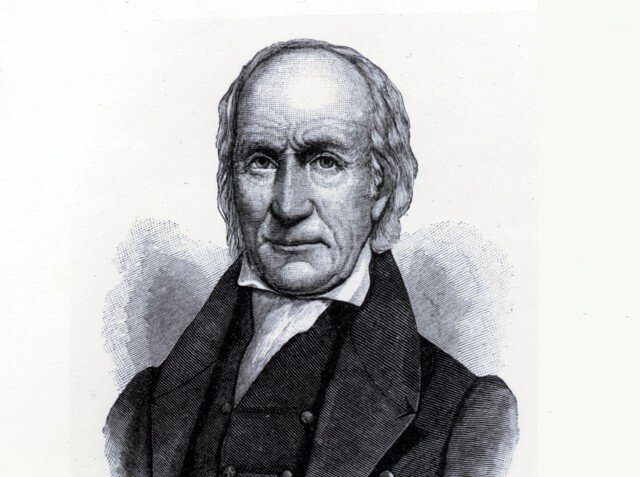

John Leland was born in Grafton, Massachusetts, on May 14, 1754. Leland’s first experience with religious subjugation happened when he was only three years old. Leland’s father desired to see his son baptized and sent for a minister to baptize him as well as several of Leland’s other siblings. Leland found out that the minister was coming to their home to baptize him and the idea of baptism terrified him. He said:

“I was greatly terrified, and betook myself to flight. As I was running down a little Hill, I fell upon my nose, which made the blood flow freely. My flight was in vain; I was pursued, overtaken, picked up and had the blood scrubbed off my face, and so was prepared for the baptismal water.

All the merit of this transaction, I must give to the maid who caught me, my father and the minister; for I was not a voluntary candidate, but a reluctant subject, forced against my will.”

Leland penned this account later in life. It illustrates that from an early age he felt the impact of having a religious idea imposed on him against his will and by those in authority. While he was only three years old when the event occurred, he remembered it for the rest of his life. The forced baptism helped to create in Leland a mindset that valued the will of the individual in making religious decisions and he desired to see that liberty extended to all people. This early event was a catalyst that started Leland down a path to fight for the religious liberty of the American people as whole.

John Leland did ultimately convert to Christianity when he was twenty years old. He realized that the baptism of his childhood had been forced upon him by an outside influence. He had never taken the faith that his father had been attempting to impose on him to heart. This experience taught Leland that a religion that is forced upon a person by an outside authority is not a true religion. Only when Leland voluntarily submitted himself to the tenets of the Christian faith did he begin to take the teachings to heart for himself. Leland recognized that forcing a particular religious belief or practice upon a person is ineffective and should be avoided as the imposition is ineffective and violates the will of the individual to make their own religious decisions.

It must also be noted that John Leland was a Baptist. Leland’s Baptist roots not only provided him with a vibrant and growing religious community to back his future work, but also a solid theological foundation from which to launch an effort to see religious freedom guaranteed in America. During Leland’s years, the Baptists were not a popular religious group but rather seen as a menace by the more established and state run denominations. This repression by the state of his religious group pushed him to take action on behalf of Baptists and other religious minorities.

Virginia: Leland’s spark

The newly married John Leland moved to Virginia with his bride in 1776. He quickly discovered that Virginia was on the frontlines of the battle in deciding how the church and the state should relate to one another. In Virginia, the Episcopal Church had been established by the government as the official church of the state. Early in Virginia’s history, the government passed laws intended to deeply entrench the state supported church and restrict the growth and propagation of other denominations. These laws were not heavily enforced in Virginia’s early years, but by the time Leland reached the state the government had begun to crack down on dissenters. Among these dissenters were Leland’s Baptists.

The wealthy state of Virginia had seen an increasing number of people moving into the state to establish homes and businesses. These people brought with them an ever increasing diversity of religious denominations. The new and growing religious diversity in Virginia began to threaten the state supported church as they saw their monopoly over religion slipping away and along with it a potential steady stream of income through taxes. This threat led to ever increasing persecution of those who did not hold to the religious beliefs of the state church. Leland, as a Separate Baptist, was part of a group that was among the most heavily persecuted.

It was into this volatile environment that John Leland moved and chose to begin his ministry. He was ordained in a church at Mount Poney and he began a fifteen year ministry in the state of Virginia. His time in Virginia was not without difficulties. Leland himself felt the heat of the Anglican persecution. Once, while preparing to baptize a woman, he was bullied by the woman’s husband who did not want the baptism because of its violation of Anglican doctrine. The angry man threatened the preacher with a gun, but Leland went forward with the baptism. This sort of religious oppression was not something Leland kept quiet about and he stated that each person possesses a “liberty of conscience” which is an “inalienable right that each individual has, of worshipping his God according to the dictates of his conscience, without being prohibited, directed, or controlled therein by human law, either in time, place, or manner.”8 He believed that each person had a right to worship God as they saw fit and that the government and state run churches should not be able force their religious views onto an individual or a denomination.

“Every man must give account of himself to God, and therefore every man ought to be at liberty to serve God in a way that he can best reconcile to his conscience. If government can answer for individuals at the day of judgment, let men be controlled by it in religious matters; otherwise, let men be free.” — The Rights of Conscience Inalienable.

Leland and Madison

John Leland’s victories for the cause of religious liberty in Virginia opened up an even greater door for him. The influence and relationships that he had built during the Virginia struggle would allow him to transition to fighting for the issue on the national stage. The year 1787 saw the establishment of the United States Constitution. It was an important step in developing the legal and political framework necessary to see the young nation survive and thrive. Leland recognized the importance of the document, but he was not completely satisfied with it. He even went so far as to use his considerable influence to mount a campaign against the ratification of the document. His reason for campaigning against the document was due to its lack of a guarantee of religious liberty. The Virginia Baptists again sought to have their voices heard by putting John Leland at the forefront of the issue. Leland was to run against James Madison in an effort to be elected to the ratifying convention.

While John Leland executed his campaign, he wrote down a list of ten objections that he and the Baptists had to the new Constitution. Among those issues was lack of a guarantee of religious liberty in the document. James Madison realized that Leland wielded a great deal of influence over the Virginia Baptists. He recognized that without the support of the Baptists, his odds of being elected to the ratifying convention were greatly diminished. Madison requested a copy of Leland’s objections to the Constitution so that he could review them. Madison desired to have Virginia accept the Constitution and recognized that an influential voice like Leland’s could sway the Baptist vote in favor of the document. This led to Madison and Leland engaging in a great deal of political wrangling as each sought to insure their causes would be heard.

Leland and Madison met personally to discuss the issue of the Constitution a number of times. During their meetings they worked out the details of what would be necessary to gain the support of Virginia Baptists for the Constitution. After their meetings, Leland delivered a promise to Madison that he would have the support of Virginia Baptists. With the confirmation that Madison would indeed continue to fight for religious liberty at the ratifying convention, Leland dropped out of the race and offered his endorsement to Madison.

John Leland understood the importance of the Constitution to the young United States. Leland also realized the power of including a clause guaranteeing religious liberty in the document and how such a clause would firmly establish the idea of religious liberty in the minds of future generations. He was willing to run for the ratifying convention against a friend and ally and use his influence with Baptists in order to see the cause of religious liberty get a voice on the national level.

John Leland and a group of Virginia Baptists were instrumental in seeing the establishment clause included in the Constitution. It was a minority Christian denomination that fought hard to make sure that government would stay out of religious affairs and leave religion to the conscience of the individual. The establishment clause was born out of a need to keep the government from endorsing or establishing a state church. Those 18th century Virginia Baptists wanted to be able to practice their faith freely and without the government imposing a set of values on them or favoring one church over the other through taxation and that’s why they fought for the establishment clause. Their work would help set the stage for the vibrant religious landscape that exists in America today where people of all faiths and cultures are free to worship and to advocate according to the dictates of their faith and their conscience.

It’s worth taking a few minutes to read some of the words Leland wrote about religious liberty. It’s especially telling to see that he wasn’t threatened by religious views different than his own and wanted all religions to have an equal playing field on the American cultural landscape.

“Every man must give an account of himself to God, and therefore every man ought to be at liberty to serve God in a way that he can best reconcile to his conscience. If government can answer for individuals at the day of judgment, let men be controlled by it in religious matters; otherwise, let men be free.” -John Leland, “The Rights of Conscience Inalienable”

“Religion is a matter between God and individuals: the religious opinions of men not being the objects of civil government, nor in any way under its control.” — -John Leland, “The Rights of Conscience Inalienable”

“Uninspired, fallible men make their own opinions tests of orthodoxy, and use their own systems, as Pocrustes used his iron bedstead, to stretch and measure the consciences of all others by.” -John Leland, “The Rights of Conscience Inalienable”

“Is uniformity of sentiments, in matters of religion, essential to the happiness of civil government? Not at all. Government has no more to do with the religious opinions of men, than it has with the principles of mathematics.” -John Leland, “The Rights of Conscience Inalienable”

“Let every man speak freely without fear, maintain the principles that he believes, worship according to his own faith, either one God, three Gods, no God, or twenty Gods; and let government protect him in so doing, i.e., see that he meets with no personal abuse, or loss of property, for his religious opinions.” -John Leland, “The Rights of Conscience Inalienable”

The bottom line is that historically, it has been religious minorities who fought the hardest for religious freedom for all. For whatever reason, some of this has been lost today. Some denominations and religious leaders have decided to make their beds with politicians and political parties and the result has been a church in America that has lost its unique voice in an ill fated and illusory effort to hold power. American Christians would do well to recover the spirit of the 18th century champions of religious liberty who used their minority position to advocate not just for their own rights but for the rights of conscience of all Americans no matter their religious preference or lack of religious preference. For religious Americans, insuring the rights of others to practice their faith according to their conscience also insures their own freedom of religion. A threat to religious liberty for one is a threat to religious liberty for all and if the dominant religious group does not recognize this, they will pay for it when the balance of power shifts away from them as it has been doing for a couple decades now.

By way of conclusion, I want to share a portion of a letter written by an even older Baptist, Roger Williams. He too was a champion for religious liberty and provides a very apt metaphor for how church and government should relate with both working together for the common good of the people and respecting the unique place in society that each institution holds.

“There goes many a ship to sea, with many hundred souls in one ship, whose weal and woe is common, and is a true picture of a commonwealth, or a human combination or society. It hath fallen out sometimes, that both [Catholics] and protestants, Jews and Turks, may be embarked in one ship; upon which suppose and I affirm, that all the liberty of conscience, that ever I pleaded for, turns upon these two hinges — that none of the [Catholics], protestants, Jews, or Turks, be forced to come to the ship’s prayers or worship, nor compelled from their own particular prayers or worship, if they practice any. I further add, that I never denied, that notwithstanding this liberty, the commander of this ship ought to command the ship’s course, yea, and also command that justice, peace and sobriety, be kept and practiced, both among the seamen and all the passengers. If any of the seamen refuse to perform their services, or passengers to pay their freight; if any refuse to help, in person or purse, towards the common charges or defense; if any refuse to obey the common laws and orders of the ship, concerning their common peace or preservation; if any shall mutiny and rise up against their commanders and officers; if any should preach or write that there ought to be no commanders or officers, because all are equal in Christ, therefore no masters nor officers, no laws nor orders, nor corrections nor punishments; — I say, I never denied, but in such cases, whatever is pretended, the commander or commanders may judge, resist, compel and punish such transgressors, according to their deserts and merits.” Roger Williams in “A Letter to the Town of Providence,” dated January 1654

References

Books

Armstrong, O.K. and Marjorie. Baptists Who Shaped a Nation. Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 1975.

________. The Indomitable Baptists. Religion in America, ed. Charles W. Ferguson. Garden City: Double Day and Company. inc, 1967.

Backus, Isaac. A History of New England. Newton: Backus Historical Society, 1871.

________. Your Baptist Heritage. Little Rock: The Challenge Press, 1976.

Burrage, Henry S. A History of the Baptists in New England. Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, 1894.

Cathcart, William. Baptist Patriots and the American Revolution. Grand Rapids: Guardian Press, 1976.

Dawson, Joseph Martin. Baptists and the American Republic. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1956.

Durso, Pamela R. and Keith E. Durso. The Story of Baptists in The United States. Brentwood: Baptist History and Heritage Society, 2006.

Eckenrode, H.J. Separation of Church and State in Virginia: The Baptists. New York: Da Capo Press, 1971.

Goodwin, Everett C., ed. Baptists in the Balance. Valley Forge: Judson Press, 1997.

Leland, John. The Writings of the Elder John Leland: Including Some Events in His Life. New York: G. W. Wood, 1845.

Little, Lewis Peyton. Imprisoned Preachers and Religious Liberty in Virginia.

Lynchburg: J.P. Bell, 1938, 117.

McBeth, H. Leon. The Baptist Heritage. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1987.

Newman, Robert C. Baptists and the American Tradition. Des Plaines: Regular Baptist Press, 1976.

Semple, Robert B. History of the Rise and Progress of the Baptists in Virginia. Richmond, 1810.

Wood, James E. Baptists and the American Experience. Valley Forge: Judson Press, 1976.

Articles

Coker, Joe L. “Sweet Harmony vs. Strict Separation: Recognizing the Distinctions Between Isaac Backus and John Leland.” American Baptist Quarterly 16 (1997): 241–250.

Conn, Joseph L. “Legacy of Liberty.” Church and State (2004): 13–14.

Irons, Charles F. “The Spiritual Fruits of Revolution.” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 2 (2001): 159–186.

Patterson, W. Morgan. “The Contributions of Baptists to Religious Freedom in America.” Reivew and Expositor (2000): 23–31.

Wardin, Albert W. “Contrasting Views of Church and State: A study of John Leland and Isaac Backus.” Baptist History and Heritage (1998): 12–20.

Historical Documents

Letter from George Washington to George Mason. October 3, 1785, Library of

Congress.

Madison, James. “A Memorial and Remonstrance.” December 10, 1785, Library of Congress.